IMVEPI, Uganda – Lorenjo Loburi grips a white container as red beans slosh in. The 13-year-old South Sudanese boy is at Imvepi Collection Center in northern Uganda. He balances the beans and a wide plate of ugali, an East African staple that is a starch paste made from maize flour. On the floor of a tent, he and his five siblings scramble to eat from the single dish they brought with them when they fled attacks on their village near Yei, in southern South Sudan, a month earlier.

This may be the only meal Lorenjo will eat today. It’s low on nutrition, but it’s enough to survive. In the years since South Sudan’s civil conflict erupted in December 2013, millions of people have struggled to get enough food. The fighting stemmed from a political dispute between the president and his former deputy, though the conflict has since splintered, involving multiple opposition groups and covering much of the country.

Lorenjo’s oldest sister, Agnes Akello, is just 17. She led her five younger siblings by foot into Uganda, with just one dish and whatever they were wearing. Their mother ran a different direction when they heard gunshots in their village. They haven’t heard from their father, who is in the military, for a long time.

“I don’t know how I will feed my younger ones,” Agnes said. “This is an experience I have never gone through.”

Even before the recent conflict, people living in the region, which separated from Sudan in 2011 to form a new country, have suffered through decades of food insecurity. A famine declaration for a small section of the country came and went in 2017. Thanks to humanitarian missions and refugee support, most people are getting just enough to survive, but little more.

And these prolonged periods of persistent undernutrition come with long-term effects for individuals – and for a country. The stunting that can occur in children who consistently do not get enough nutrients translates into lower levels of literacy, less productivity and an even slower economic recovery than the country was already facing.

“It’s pretty clear that even a short-term shock such as a famine or Zimbabwe’s civil war can lead somebody to be stunted,” said Harold Alderman, a Harvard economist and expert on how malnutrition can affect economic growth. While stunting can limit future physical productivity, “the real issue is that it has been shown in many studies that they will also have less education. And for every year that they’re in school they’ll learn less. That then means that in 15 years from now, 20 years from now, they’ll have a less skilled labor force.”

For South Sudan that means, even if peace returns, the country – with what are likely to be high stunting rates – will face an uphill battle to revive its shattered economy and escape a cycle of persistent food insecurity.

Hunger and conflict

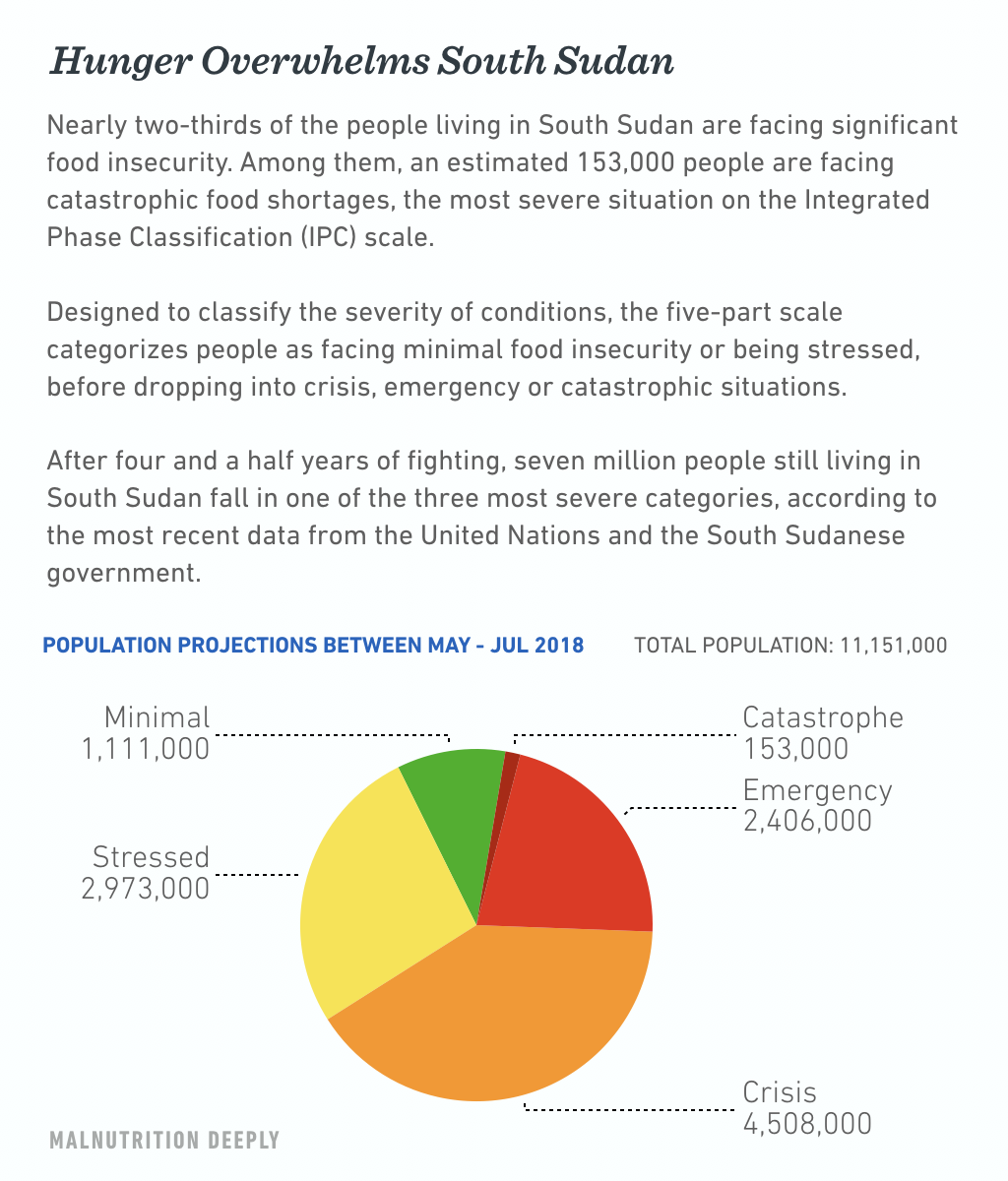

In South Sudan, the scale of food insecurity is immense. The latest U.N. analysis found more than 7 million of the estimated 11 million people living there are now classified under the three worst levels of food insecurity: crisis, emergency and catastrophe.

Fighting has erupted periodically, particularly in rebel-supporting areas, making it difficult for communities to plant crops or protect livestock. Humanitarian agencies are also regularly stalled, interrupting vital relief supplies and exacerbating food insecurity.

It is hard to know how many children will emerge stunted from South Sudan’s conflict, though the last nation-level data from South Sudan found that in 2010, about 30 percent of children between six and 59 months old had evidence of stunting. Those numbers have almost certainly increased since the current conflict began in 2013, if they were even accurate to begin with.

The numbers are measured by comparing a child’s height against an average that children should have reached for their age. But determining that average is complicated.

“If you compare a child in Spain, or a child in Nairobi, or a child in South Sudan, it will be compared to this global average height measurement,” says Jose Luis Alvarez Moran, senior nutrition advisor at the International Rescue Committee. And critics of the approach say it may lead to inaccurate counts. In South Sudan – a country with some of the tallest people in the world – it’s possible the number of children with stunting could be far higher than official figures, said Dina Aburmishan, a nutritionist with the World Food Program. But even if they are suffering from stunting, their height measurements might not show it.

Lingering impact

If ongoing attempts to strike a peace deal continue to falter, hunger is likely to persist for some time in South Sudan, which means even more children are likely to be stunted – whether aid agencies are able to measure them or not.

And that means that even if peace does return to South Sudan, economic recovery might not follow very quickly. Studies have indicated a country’s gross domestic product can dip by 12 percent with high populations who are stunted. As well, a person with stunting is expected to earn about 22 percent less, according to Alderman. In a fast-growing economy, Alderman says those who are stunted can often be left behind.

“The faster the economy’s growing the greater the disadvantage that the child has, because they can’t take advantage of the growth,” he said.

For the children who are already affected, there is little anyone can do to help. “For acute malnutrition, we have a treatment and the child feels better,” Aburmishan said. But most of the research has shown that once a child has experienced stunting, there is no fixing the problem. The physical and cognitive effects are thought to be irreversible.

“The only cure is prevention,” Aburmishan said. That’s what humanitarian agencies are trying to do through food drops, vaccinations, community education programs on nutrition and support for breastfeeding mothers.

Alderman said it’s also been shown that stunted children can in some cases catch up – but, that’s hugely dependent on the existence of supports in place in schools and society that offer extra support to those students.

“There are studies that have followed Jamaican children for 25 years afterwards,” he said. “If they’re given a lot of resources, lots of time and stimulation they can catch up cognitively. But an economy that has been shattered doesn’t have the resources.” He said it might be feasible to take on these efforts for a handful of children, “but there’s no way that a country can get that type of resources to thousands or tens of thousands of children.”

Critical interventions

There are some steps aid agencies can take, even in the midst of a conflict, to reduce the long-term impacts of malnutrition.

Mena Adalbert, nutrition coordinator for the International Rescue Committee in South Sudan, said one of the key preventative measures is to ensure children are not becoming even more malnourished due to disease or sanitary conditions. When children rely on dirty drinking water, diarrhea or other diseases can mean they gain even fewer nutrients from the little food they’re eating.

There’s also evidence that working with mothers to ensure they breastfeed their children – at least for the first six months – can reduce the likelihood a child will become chronically malnourished. Moran says programs educating mothers and providing them with support can improve the long-term situation. But only if aid agencies can access those mothers and if they have the funding to mount the programs.

These interventions are also crucial because stunting can become cyclical. Woman who are stunted due to chronic malnutrition are more likely to have children who will be stunted, “creating an intergenerational cycle of poverty and reduced human capital that is difficult to break,” according to a study on stunting in developing countries. This can be both because of genetics and socioeconomic circumstances: Not only are children of stunted mothers often born smaller, but they are often born into circumstances of poverty and deprivation, according to another study on childhood stunting.

Experts say what is most critical now is adequate funding for all these humanitarian programs and preventative measures, mixed with efforts to keep those who have experienced stunting from being left behind. But only about half of the money needed for South Sudan’s immediate humanitarian response plan has come through – and that does not even take into account the long-term development programming that might help a stunted child catch up.

This article was originally published on Malnutrition Deeply.