There has been an ongoing debate over the British government’s commitment to spend 0.7 percent of the U.K.’s gross national income (GNI) on foreign aid. First achieved in 2013, and enshrined in law by the Conservative-Liberal coalition in 2015, the U.K. was the world’s third largest donor of foreign aid in 2016, after the U.S. and Germany.

The 0.7 percent target has received much criticism, especially from right-wing tabloids, as well as within the Conservative party, and even the cabinet.

But in late April, the prime minister, Theresa May, confirmed that “the 0.7 percent commitment remains, and will remain.” Given such a firm commitment regarding the volume of U.K. aid, a more sensible debate is needed on what to spend this vast amount of money – around £12bn in 2016 – on. In particular, calls for using aid to support refugees arriving in the U.K. need scrutiny.

What Counts as Foreign Aid

It is worth clarifying what foreign aid can and can’t be spent on. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee (DAC), the organization that coordinates the activities of Western aid donors, sets the guidelines on what can be counted as aid – or “official development assistance”, to use DAC jargon.

Most people would assume that what is reported as foreign aid by a donor actually goes to support development projects in poor countries. In reality, however, a number of expenditures can be classified as foreign aid, giving donors large scope in how to organize their international development activities.

Expenditures such as membership fees of certain international organizations, peacekeeping, promoting the peaceful use of nuclear energy, scientific cooperation, and even debt relief can all be classified as foreign aid. A donor’s administrative costs related to aid delivery, and the promotion of development awareness within the donor country can also be reported as aid, and so can the costs of caring for refugees in the donor country (during the first year following their arrival).

NGOs have been highly critical about reporting refugee costs, debt relief and donor administrative expenses as foreign aid. Some have been running a strong Europe-wide campaign for a decade now to exclude these expenses from aid-eligible costs, and force donors to focus on “genuine” aid. They define this as aid that is actually spent in a recipient country, rather than the donor country.

Aid Flows Shifting

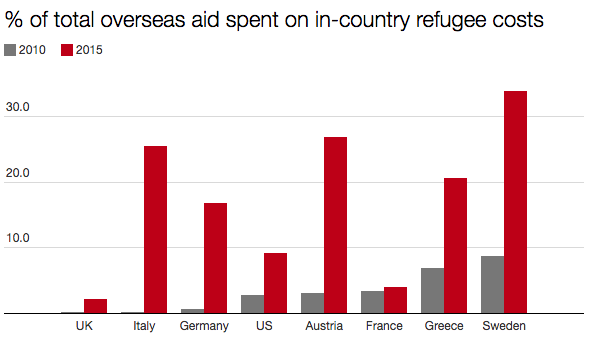

Since 1988, donors have been able to include the costs of caring for refugees – such as costs for housing, refugee camps, education and living allowance for asylum seekers – as part of their aid. Many have, but Europe’s refugee crisis has led to a significant increase in this practice.

According to new data recently released by DAC, Germany’s foreign aid, for example, jumped from almost $18 billion in 2015 to more than $24.5 billion in 2016, mainly due to an increase in refugee costs. In-country donor refugee costs accounted for 38 percent of all aid in Austria in 2016, and 34 percent, 25 percent and 22 percent in Italy, Germany and Greece respectively. The average for all Western donors was close to 11 percent in 2016.

Source: OECD DAC (2015 data is preliminary)

The U.K. has so far been among the few donors who have tried to keep their foreign aid as “genuine” as possible, and did not include many refugee costs in these statistics.

Historically, refugee costs made up around 0.1 to 0.3 percent of all U.K. aid, and while an upward trend began after 2013, it was still among the lowest among Western donors at 2.2 percent in 2015. This means that there is considerable scope for the U.K. to divert a part of its aid budget to fund the costs of hosting new refugees.

Short-term Thinking

There are, however, a number of reasons why the government should not give in to this temptation.

First, Britain has carved out a reputation for itself as a highly effective and generous donor, a leading power in global development. The soft power and influence that this gives Britain should not be underestimated. In the past decade, the U.K. has clearly been able to punch above its weight in setting the agenda of the international development system.

In a recent paper, together with Simon Lightfoot and Emma Mawdsley, I argued that the U.K.’s reputation is already under threat due to Brexit. The government should not do even more to undermine it by cutting genuine aid to spend it on hosting refugees in the U.K.

Second, diverting a part of the aid budget to fund refugee costs could embolden other demands for diverting aid. Some of these, such as the foreign secretary Boris Johnson’s idea of buying off Eastern European E.U. members to support U.K. demands during the Brexit negotiations, are nonsensical. Others, such as aligning U.K. aid and trade policy more closely have merits, but require detailed scrutiny. The poorest countries could be worse off from such realignment, something that goes against what British aid has stood for so far.

This brings us to the third reason: cutting genuine aid perhaps poses even more dilemmas than increasing it does. Questions such as which partner countries should be dropped, or which programs terminated, are highly complex. Beyond the ethical dilemmas of leaving the poor behind, stopping aid programs requires careful planning, phasing out periods and a cautious management of the relationship with the (former) partner. If it is not careful, Britain may end up hurting some of its long-term interests.

Given the amount of pressure the government faces to maintain 0.7 percent GNI aid spending, some changes in how that aid is used are inevitable. But this should be done based on a thorough evaluation of British interests, as well as the strengths and weaknesses of British aid, and not short-term political interests and following what other donors are doing.

This story was originally published on The Conversation and is reproduced here with permission.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Refugees Deeply.

Never miss an update. Sign up here for our Refugees Deeply newsletter to receive weekly updates, special reports and featured insights on one of the most critical issues of our time.