At least 200 million women and girls living today around the world have undergone female genital mutilation (FGM), the ritual cutting or removal of female genitalia. And yet, information on the procedure – practiced widely in parts of Africa, the Middle East and Asia – has long been patchy, usually analyzed only on a country-by-country basis. Now a new global synthesis report by the Population Council for the first time gathers together evidence on FGM prevalence in 29 countries. Published in August, the report offers new insights into the way the practice is changing from culture to culture, including the fact that girls are now undergoing FGM at a younger age.

Jacinta Muteshi-Strachan, Nairobi-based research program director on FGM for the Population Council, spoke with Women & Girls Hub about the report’s conclusions, highlighting five key findings from the research.

1. Prevalence is down but the picture is incomplete

Jacinta Muteshi-Strachan says, “There are 29 countries included in this report. Fifteen of these countries show no clear evidence of progress, while in 14 countries the practice appears to be declining. The data also gives an indication of prevalence within each country. While less than 5 percent of women in Cameroon, Uganda, Niger and Ghana have undergone FGM, the practice is nearly universal in Djibouti, Egypt, Guinea, Sierra Leone and Somalia. Two-thirds of all women who have undergone FGM live in just four countries: Egypt, Ethiopia, Nigeria and Sudan. More than one-quarter come from Egypt alone.”

Muteshi-Strachan adds, “One of the most important takeaways from this research is the fact we have absolutely no data from some countries where we know FGM is practiced. Getting data from these places should be prioritized to build a better global picture as soon as possible. These countries include places such as India, Iran, Malaysia, Pakistan and even most recently Dagestan, where we know girls are regularly undergoing FGM but there is no national data.”

2. Increasingly, girls are undergoing FGM at a younger age

In nearly half of the countries with information on age at cutting, the majority of girls were cut before the age of five. Even in places where the practice commonly occurs at older ages, there has been a downward shift in the average age at which girls are cut. According to 2014 Demographic and Health Survey data in Kenya, older women (ages 40–44) report that they had been cut at around age 15, but the younger generation (ages 15–19) was cut on average at around age 10.

Muteshi-Strachan says, “This is especially important to understand when girls are most commonly at risk. According to the report, one reason FGM is performed on girls at young ages is that it can be done more discreetly, a particular advantage in areas where anti-FGM campaigns or legal restrictions are prominent. Other reported reasons are that younger girls heal more quickly and are less resistant.”

3. Both men and women want FGM to stop

According to Muteshi-Strachan, one of the most important findings of the report is the fact that many women and men are open to stopping the practice, offering a promising window for change.

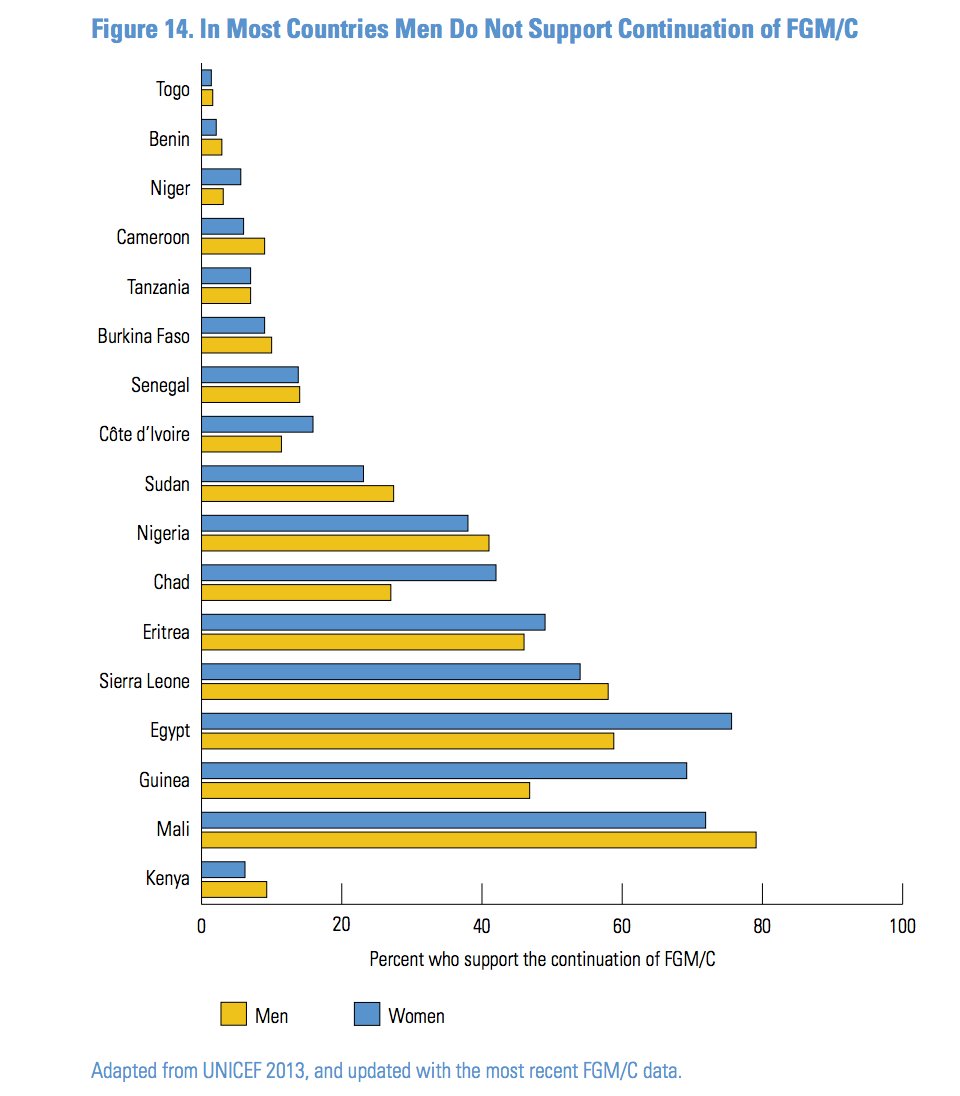

FGM is often thought to be a symbol of the patriarchal oppression of women. As such, there is an expectation that support for the practice among men is high. The latest data, however, refutes this. The majority of men in many countries report that they do not support the continuation of FGM (see figure below). In fact, in Egypt, Guinea, Ivory Coast, Chad, Eritrea and Niger, fewer men than women report support for the continuation of FGM, raising some important questions around how much influence men have on the tradition.

Muteshi-Strachan says, “Much of the work done on FGM targets women and rarely targets men around ending the practice. FGM is traditionally seen as women’s business, carried out against women by other women. However, if we are saying women are being cut because men require it for marriage [a claim that is often made by women doing the cutting], then it makes sense to include men in the conversation. The fact that so many men in these communities are open to change should be harnessed to bring about change.”

4. FGM is on the increase in diaspora communities

In the past few decades, western Europe, the United States, Australia and New Zealand have absorbed large numbers of migrants or refugees from countries in which FGM is practiced. A 2016 study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that in 2012 about 513,000 girls and women in the United States were at risk of FGM, meaning that they had potentially undergone the practice in the past or were at risk of undergoing it in the future. Of those at risk, about 169,000, or 33 percent, were younger than 18 years old.

Muteshi-Strachan says, “Up until recently, people thought about this as a problem that affects only women and girls in Africa and the Middle East. With increasing migration this is becoming a global issue. Many communities in more developed nations send their daughters back to their countries of origin for FGM. Understanding this can also help us tackle the problem.”

5. Education and economic development could be key to bringing about change

Another area of study has been the influence of urbanization, education and economic development on FGM preferences. One finding from research on the impact of community on the prevalence of FGM is that interpersonal relationships can often influence someone to act against their personally held beliefs. For example, in some cases women don’t agree with FGM but are persuaded to cut their daughters because of pressure from other members of the community.

Muteshi-Strachan says this finding could be the key to understanding how to change FGM practices and who to target. In Egypt, for instance, recent reductions in girls’ risk of undergoing FGM has been linked not just to an increase in their mothers’ education levels, but more broadly to that of women throughout the community.

“The next piece of work we produce will be on evidence of change,” says Muteshi-Strachan. “We know there are many interventions underway and they vary between communities. If we see a decline, we want to know what caused that decline and which interventions were most effective.”